Note on Photographic Facsimiles, Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts

No matter the care put into transcribing a text, a gap

still remains between the reader and the physical document. The use

of photographic facsimiles in this volume narrows that gap but does

not eliminate it. This note explains how these photographs were

created and prepared for publication and identifies some of their

limitations.

Creating the Photographs

The textual photographs herein were created specifically

for this publication and its online counterpart by Welden C.

Andersen and, in the case of the images of the printed version of

the Book of Abraham, members of the preservation staff at the Church

History Library. Andersen used a Hasselblad H3DII-39 multishot

camera equipped with a Hasselblad HC 120mm f4 macro lens. By taking

a sequence of four photographs, this camera captures red, green, and

blue data for every pixel, whereas a single-shot camera records only

one color per pixel. The four-shot technology therefore captures

much more detail. The lens is optimized for extremely close

focusing, allowing for images of documents that can resolve to the

level of individual fibers of the paper. Each of the digital images

produced by the camera comprises approximately 229 megabytes of

information. Though the resolution of these images must be reduced

significantly for print publication, the Joseph Smith Papers Project

retains the original, full-resolution files, which will allow

researchers to view extremely detailed electronic images. Indeed, a

primary purpose for creating these photographs was to minimize the

need for researchers to consult the original documents.

During photography, the manuscripts were positioned on a

low, leveled table. Studio lights diffused by a fabric screen were

used to illuminate the subject, and a computer was attached to the

camera to process and store the images. The camera was positioned

about four feet above the table on a camera stand. Andersen

hand-focused each photograph and then remotely triggered the

shutter. After ensuring the quality of the first image on the

computer monitor, he made a second exposure to create a security

backup copy for each image.

Andersen followed standard professional procedures to

achieve the highest accuracy in color, tone, contrast, and exposure.

Before photographing and any time he adjusted lighting, exposure, or

document angle, he calibrated and corrected color using a color test

card and color adjustment software. This eliminated any bias of the

camera sensor and the light source, meaning that the colors captured

in the photographs are as close as possible to the colors of the

documents as they exist today.

Preparing the Photographs for Print

Publication

Charles M. Baird, a prepress specialist with the

Publishing Services Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of

Latter-day Saints, prepared the images for printing. Following

standard prepress methods, Baird reduced the images to fit the page

size in this volume at a

resolution of approximately 300 dpi and converted the images from

the color format stored by the camera (red, green, and blue) to the

colors used in printing (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black).

As mentioned earlier in this note, the documents featured

in this volume were photographed resting on a table. For aesthetic

reasons, Baird used photo-editing software to digitally remove the

table from the background and to add a thin shadow around the edge

of each image.

Except as described in this note, the textual photographs

in this volume have not been altered.

Limitations of the

Photographs

Even careful photographs can underplay important features

of the original document. Four categories of such features are worth

noting here.

First, the documents in this volume are of many different

sizes, though the image sizes used herein to maximize readability in

the available space may give the illusion that the documents are

roughly the same size. Readers should carefully consult the physical

description of each document to determine its size.

Second, some documents featured in this volume include

unconventional writing patterns that require special treatment. The

Egyptian Alphabet documents, for example, are written on large

sheets of paper, some of which were folded in half to resemble a

book. On a few pages, writers wrote all the way across the sheet, so

that a single line spans both the left and right pages. In an effort

to represent the record as it actually appears and to preserve the

detail of individual words, such sheets are artificially divided in

half and presented in this volume on two successive spreads—the

first containing the top half of the sheet and its transcription,

and the second containing the bottom half and its transcription.

Third, some nontextual features of the manuscripts are

represented in the photographs but not commented on in the

transcription or annotation. For instance, some pages show

bleed-through or ink transfer from adjoining pages, but these marks

are not noted.

Fourth, some documents herein contain multiple blank

pages, which are not reproduced in this volume. Readers wishing to

consult the blank pages of these manuscripts can view them in their

entirety at josephsmithpapers.org.

Techniques Used to Recover Canceled

Text

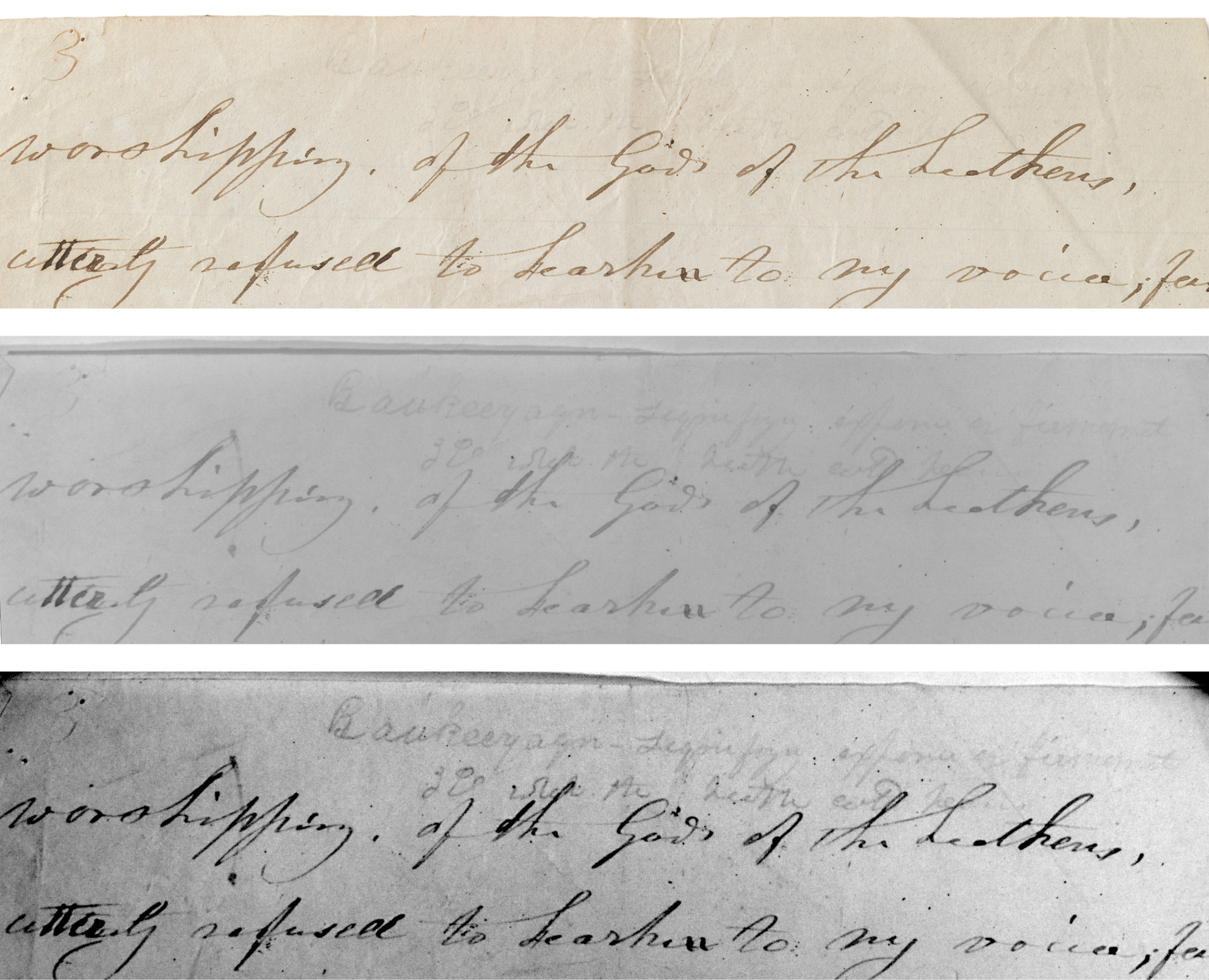

Transcribers for this volume used multispectral imaging

and photo-editing software to recover obscure text or study

characteristics of the manuscripts. Multispectral imaging, which

uses different wavelengths of light to show features that cannot be

seen by the human eye, revealed text on one of the Nauvoo-era Book of

Abraham manuscripts that was otherwise unreadable. (See

fig. 1.) Similarly, the two concentric circles etched into a page of

Notebook of Copied Egyptian Characters, circa Early July

1835, are difficult to see in an ordinary digital image.

Photo-editing software allowed the page to be enhanced so that the

circles could be more closely

examined.

Fig. 1. A faint graphite

inscription at the top of a page of one of the Nauvoo-era manuscripts of the Book of Abraham is nearly invisible to

the naked eye (top). Multispectral imaging made the inscription less

obscure (middle), and the use of photo-editing software allowed

editors to read and transcribe it

(bottom).